de Monica Ciobanu

Education in Western democratic societies is broadly focused on combining the goals of providing theoretical and practical knowledge with acquiring and practicing the skills of citizenship. In this context, teaching history is more than a linear narration of events, and must include themes and stories reflecting individuals and movements that fought for and helped bring social justice and political equality to their respective countries. In contrast, societies exiting the totalitarian Soviet system perceive education as finally liberated from government political and ideological interference where teaching history had been made to serve the interests of the party, that is, history as a tool of propaganda. This freedom, however, is itself problematic: how to teach the past and, particularly, the immediate past. Of course, teaching controversial aspects of a society’s history can pose difficult questions even in democratic settings. Many Americans still feel uncomfortable, for example, in discussing the history of slavery or the treatment of Native Americans. However, in Eastern Europe the debate of the recent communist past raises even more delicate dilemmas since many of the victims and perpetrators are alive and, in the case of the latter, many continue to be influential. The case of teaching history in post-communist Romania represents a good illustration of an ongoing discussion of confronting the past and building democracy in which educators introduce a pedagogy of truth and justice in the classroom.

The Teaching of History Under the Communist Regime and its Legacies

The repression exercised by totalitarian Soviet systems was all-pervasive in Eastern Europe during the period of communist domination. Together with the institutions of politics, economy, culture, and the family, the educational system was subjected to a program of total

societal mobilization as required by ruling Marxist-communist ideology. The teaching of humanities and social sciences and the textbooks used at both primary school and high school levels were principally focused on a constructed narrative of victorious class struggle against the class enemy and the concept of the socialist system as the inevitable end of history.

The best example of how one-party states in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe used education as an instrument for political socialization and to create their own legitimacy is provided by the teaching of history. Romania was not an exception to this. During the 45 years of the country’s communist experience, two stages of communist historiography can be distinguished. Between 1944 and 1965, the main themes were communist internationalism and the positive role played by the Soviet Union. The second stage between 1965 and 1989 reflected the development of what came to be known as nationalist communism (Papacostea, 2004, pp. 223–224). This was very much the result of former president Nicolae Ceausescu’s promotion of an extreme nationalist-communist doctrine that was used in elaborating and sustaining a cult of personality. History textbooks expressed a myth of Romanian exceptionalism based on the claim that the Romanian state was both one of the oldest in Europe and that it had a special role to play in the world. National history was presented as a series of successive glorious battles culminating in the victory of the Communist Party and Ceausescu’s leadership. It was described as the “golden era” of Romanian history.

After the collapse of the communist regime in 1989, Romanian historians were reluctant to recalibrate or rewrite recent history. They claimed that it was too early to analyze the communist period objectively and argued also that they lacked access to relevant documentation. In one of the first revised history textbooks, designed for the 12th grade in 1992, for example, the 45 years of communist rule were covered in only ten pages. In comparison, a hundred pages were devoted to the 25 years of the interwar period (Boia, 2001, p. 233). It was not until four years later, and then at the recommendation of the European Union Council, that the Ministry of Education addressed the issue of designing new history textbooks for different grade levels that would encourage critical thinking and provide flexibility for a critical interpretation of national history. The new textbooks were required to reflect the values of a democratic society and to include voices that were marginalized under communism—for instance, ethnic and religious minorities, women, and local communities. The task of reforming textbooks, undertaken by a team of historians, began in 1998 and was finalized in 2000 when, for the first time, the old practice of providing only a single textbook was replaced by an array of alternatives. However, these new textbooks generated virulent attacks from members of parliament, particularly representatives of the Social Democratic Party (PSD), the transformed successor to the Communist Party, and from professors of history affiliated with the Romanian Academy who had been trained in communist historiography. The two groups joined forces and vehemently criticized the new publications for failing to transmit precise historical information to students, for their openly critical analysis of national heroes and other historical figures, for raising doubts in respect to national identity, and ultimately for undermining what was taken to be the goal of education—that is, to promote patriotic loyalty (Paraianu, 2005). After a parliament motion against the government by PSD and other parties and a scandal in the parliament, one textbook lost its authorization to be integrated into the national curriculum (Culic, 2005).

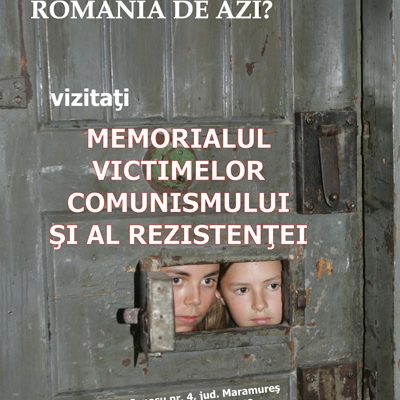

The Sighet Memorial Summer School

In the absence of professional commitment among academic historians or political commitment among the political class, civil society groups began to pursue the task of undertaking a systematic and critical analysis of the recent past in the 1990s. One of the most dedicated groups was the Civic Foundation Academy, set up in 1994 and run by a well-known poet and former dissident, Ana Blandiana. The primary goals of the foundation—to promote civic education and revise the country’s history falsified by the communist regime—were accomplished through the Memorial to the Victims of Communism and of the Resistance in Sighet (a small town located in the northern part of Romania at the border with Ukraine) and through the International Center for Studies of Communism with headquarters in Bucharest. Blandiana and her partner, novelist Romulus Rusan, were not intimidated by political pressure or xenophobic campaigns by former communist and nationalist forces and managed to establish the memorial in 1997, at which time it was designated a national historical site. The memorial’s motto, written by Blandiana—“When justice does not succeed in being a form of memory, memory itself can be a form of justice”—accurately suggests the complex dynamic between memory, the rewriting of history, and instituting justice in post-communist Romania. Sighet Memorial consists of a museum located in a building that had been operated as a Stalinist jail where pre–World War II political elites were incarcerated (see Figure 1). The history of 45 years of communism with its most significant episodes of repression, extermination, and revolt is exhibited in each of the 60 cells of the prison, portraying jails, labor camps, psychiatric asylums, places of interrogation, torture and execution, the armed resistance from the mountains, the peasants’ opposition to collectivization, the deportation of ethnic Germans and Serbs, the worker’s uprising from 1987 in Brasov, the resistance of intellectuals, dissidence, etc. In 1998 the memorial was designated by the Council of Europe along with the Auschwitz Museum in Poland and the Peace Memorial in Normandy as one of the principal memorial sites of the European continent (Memorial of the Victims, n.d.).

Since Sighet could not have been a more ideal place to bring young people together and engage their interest in the recent past, the Sighet Memorial Summer School was established and became a nontraditional classroom setting that provided teenagers between 14 and 18 years old with a unique opportunity to learn about Romania under communism. Their instructors are not only historians, sociologists, or political scientists, but also anti-communist partisans who opposed the institutionalization of the Soviet system in the late 1940s and 1950s, former political prisoners, former dissidents of the 1970s and 1980s, descendants of the victims of communism, former diplomats, artists, and film-makers. In 2007, the summer school celebrated its 10th anniversary and could count more than 1,000 participants. For the past several years the position of director of the summer school has been held by a French historian, Stéphane Courtois, the editor of the well-known and controversial Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (1999), one of the first studies that has attempted to give an exhaustive account of the Soviet gulag. In its first year, 1998, the selection of students based on lists of winners of history competitions was not found to be conducive to lively and animated debates between speakers and participants. The atmosphere was stilted and conformist, the students unaccustomed to the free-flowing expression of ideas (“Sighet Memorial Summer School,” n.d.). This was corrected the following year when a selection criterion based on an essay contest was introduced. The subjects of the essays were chosen either to test the participants’ knowledge about the past, or to provoke reflection on current contentious debates in Romanian society attributable to the communist legacy. Among the first, I should like to mention as an example the essay topic “What do I know about the communist years?” and a review of a book containing testimonies by those who suffered under communist repression. For the second theme, subjects were selected in relation to the most pressing problems of Romanian politics and society: “What is the source of extremism?”; “Can corruption be considered as the most important scourge in post-communist countries? Why?”; “Do you want to become politicians? If yes, explain why; if not, explain why.” Each annual summer school awards a number of essays that are then published as part of the “teenager series” of the Sighet Library. So far four such volumes have been published (Rusan, 1999; Rusan, 2001a; Rusan, 2001b; Rusan, 2001c).

The format of the school is organized through conferences, roundtables, workshops, documentaries, and music concerts. Since its aim is more ambitious than re-creating a local/ national memory of communism, but also to engage in a global dialogue, the pool of guest lecturers transcends national boundaries. During its 10 years of existence, the summer school has benefited from the presence of a prestigious group of visitors, including the former Russian dissident Vladimir Bukovski; writer Michel Thomas Penette, leader of the Council of Europe project “European Itineraries”; Helmut Muller-Enbergs, a researcher at the archives of the former security apparatus of East Germany; Christian Ostermann, director of the International Center of the History of the Cold War of the Woodrow Wilson School in Washington, D.C.; British historians Dennis Deletant, Mark Percival, and Tom Gallagher; Bogdan Lis and Tadeusz Fiszbach, who were both former leaders of the anti-communist Solidarity movement in Poland; Frantisek Zahradka, a former political prisoner in Czechoslovakia and founder of the Vojna Memorial; and many others.

Young participants are motivated, eager to learn, and unafraid to ask inconvenient questions (Ieronim, 2004). Stéphane Courtois has noticed that from year to year teenagers at Sighet reflect the fact that Romania is undergoing modernization. In the late 1990s, they often seemed sad and resigned. In contrast, recent participants speak several foreign languages and have digital cameras, mobile phones, and a lively interest in their country and the world around them (Courtois, 2006). But the most vivid indication of the impact that the school has over minds and hearts comes from students themselves:

“Sighet is the prison where I think of myself. I cannot say that I share memories with this place but it is where I create them…The past represents me even if I didn’t live it. The summer school in Sighet is a place of collective post-December [1989] consciousness in the search for a responsible society.”

“At the end of a special cognitive experience, each of us managed to see that believing in freedom and democracy cannot be regarded as anything but normal and it is only up to us that it doesn’t become inconceivable.”

“Each room, each cell I visited helped me… understand how lucky I am to live in a world whose values (at least at the level of principle) are not terror, fear, persecution, but freedom, justice, democracy.” (“Declarations of the pupils participant to the Summer School,” 2005)

An Optimistic View About the Future of History

The innovation of having an open and critical discussion of the communist past has not ceased with the Sighet Memorial Summer School. In January 2007, President Traian Basescu endorsed before the parliament a report issued by the Presidential Commission for the Analysis of Communist Dictatorship in Romania, almost 700 pages that address for the first time the crimes committed under communism. It was published later that year (Tismaneanu, Dobrincu, & Vasile, 2007). Some of the most significant recommendations of the report refer to issues of memory, justice, and education. Particularly emphasized are the memorialization of the victims of communism and education oriented towards the analysis of communist history in both schools and academic institutions. The reorganization of the national archives and the granting of unrestricted access to them represents for the first time a positive sign by the government that the past can be revisited without inhibition or political interference. But a genuine reconciliation with the truth of Romania’s communist past must ultimately rest with the country’s youth and its education.

References

Boia, L. (2001). History and myth in the Romanian consciousness. New York & Budapest: Central European University Press.

Culic, I. (2005). Re-writing the history of Romania after the fall of communism. History Compass: Europe, 3, 1-21.

Courtois, S. (Ed.). (1999). The black book of communism: Crimes, terror, repression. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Courtois, S. (2006, May 26–June 1). Memorialul crimelor comuniste [The memorial of the victims of communism]. Revista 22, 846. Retrieved April 17, 2008, from http://www.revista22.ro

Declarations of the pupils participant to the summer school. (2005, September 13). Retrieved January 8, 2008, from www.memorialsighet.ro/en/stiri-evenimente.asp?id=57.

Ieronim, I. (2004). Scoala memoriei de la sighet [Sighet memorial school]. Revista 22, 751, June 28- July 3, 2004.

Memorial to the Victims of Communism and of the Resistance. (n.d.). Retrieved January 5, 2008, from www.memorialsighet. ro

Papacostea, S. (2004). Istoriografie si totalitarism [Historiography and totalitarianism]. In R. Rusan (Ed.), Scoala memoriei 2004 [The school of memory 2004] (pp. 223-224). Bucharest: Fundatia Academia Civica.

Paraianu, R. (2005, November 11). The history textbooks controversy in Romania. Eurozine. Retrived January 5, 2008, from www.eurozine.com/articles/2005-11-11-paraianu.html.

Rusan, R. (Ed.). (1999). Exercitii de memorie [Memory exercises]. Bucharest: Fundatia Academia Civica.

Rusan, R. (Ed.). (2001a). Cum as vrea sa fie familia mea [How I would like my family to be]. Bucharest: Fundatia Academia Civica.

Rusan, R. (Ed.). (2001b). De unde vine extremismul? [Where does extremism come from?]. Bucharest: Fundatia Academia Civica.

Rusan, R. (Ed.). (2001c). Exercitii de speranta [Hope exercises]. Bucharest: Fundatia Academia Civica.

Tismaneanu, V., Dobrincu, D., & Vasile, C. (Eds.). (2007). Raport final: Comisia Prezidentiala Pentru Analiza Dictaturii Comuniste din Romania [Final report: The Presidential Commission for the Analysis of Communist Dictatorship in Romania]. Bucharest: Humanitas.

MONICA CIOBANU is an assistant professor of sociology in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at SUNY Plattsburgh. She has written about democratization in Eastern Europe and her current work is focused on issues of memory, truth, and justice after communism.

articol aparut in revista Democracy & Education

Jun 2008, Vol. 17 Issue 3, p58-62